I. Introduction: The “Wellbeing Cascade”

The Pāli Canon (Tipiṭaka) is the oldest record of the Buddha’s teachings and is the ultimate fount from which all Theravāda practitioners, including myself, draw inspiration, guidance, and meaning. This corpus of roughly forty print volumes, was originally orally transmitted and thus features many stylistic elements that are particularly relevant for that medium. One such element is the use of pericope, frequently repeated “stock phrases” that function as the primary building blocks for constructing the edifice of textual Buddhism. In this paper, we will pick up and get a feel for one particular building block, a passage appearing over fifty times in various contexts throughout the Pāli Canon that has become a foundational cornerstone of my personal epistemology. Beyond its personal significance, the passage provides an extremely helpful positive counterpoint to an unfortunately common malaise-inducing form of Buddhist practice that indulges in, rather than investigates, suffering.

The following quote is the most complete example of this dearly loved pericope, and will serve as a basecamp for our exploration:

There are nine habits of mind that are of great benefit. What nine? Those habits of mind that are rooted in radical awareness (yoniso-manasikāra): 1) For one engaging in radical awareness, a sense of wellbeing (pāmojja) arises. 2) Having a sense of wellbeing, joy (pīti) arises. 3) Having a joyful mind, one’s body relaxes. 4) One having a relaxed body experiences happiness (sukha). 5) For one who is happy, the heart becomes concentrated (samādhiyati). 6) When the heart is concentrated, one knows and sees in accordance with reality. 7) Knowing and seeing in accordance with reality, one becomes untroubled. 8) Being untroubled, one becomes utterly cool. 9) With utter coolness, one is truly liberated. (Dīgha Nikāya 34)

For this paper, I will call this stepwise progression of positivity the “wellbeing cascade”—a reference to a simile that the Buddha used to capture the progression’s hydraulic dynamics:

It is just like when a raincloud showers down big, fat droplets of water on top of a mountain. That water, flowing down along the slope, fills up the mountain’s creeks, fissures, and gullies. When those are full, they fill up the pools … ponds … streams … [and] rivers. When those are full, they fill up the great ocean. (Saṃyutta Nikāya 12.23).

The message of this psychological trajectory appears pragmatic, optimistic, and approachable: the Buddhist path, walkable right now, is about getting better at happiness.

In comparison with the distressing, yet common, dour approach of many vehement meditators, the “great benefit” of these nine steps seems to suggest a more compassionate approach: rather than a masochistic wallow in suffering, the Buddhist way of practice can be a sustainable training in increasingly lofty states of human flourishing. In the “Discourse on Setting an Intention,” the Buddha adds “one need not set the intention” (na cetanāya karaṇīyaṁ) for each of the affectively positive pools in this wellbeing cascade to overflow into its subsequent reservoir (Aṅguttara Nikāya 10.2). Rather, such gravitational and psychological movement is a “natural” (dhammatā) result, a predictable consequence of prior pooling. This being the case, this paper will focus primarily not on all the “creeks, fissures, … gullies … pools … [and] ponds” further downhill, but will instead, with two notable exceptions at the outset, look upwards to the raincloud and to the first puddles upon the mountain’s peak. That is, trusting in the hydrodynamics of down-flowing water to eventually issue into the “great ocean” of true liberation, we will wonder at the cloud of “radical awareness” (yoniso-manasikāra) and the first splashes of wellbeing (pāmojja) upon the mountaintop.

As just mentioned, before delving into our primary study of the precipitation that instigates our wellbeing cascade, I will address two other aspects of the simile: the mountain itself and its fifth pool. In other words, we will first ground ourselves in the terra firma of shared experience, namely, the truth of unsatisfactoriness/suffering (dukkha); then, we will take a brief plunge into its fifth pool mid-way down the cascade, the proclamation that “For one who is happy, the heart becomes concentrated.” Exploring these facets of our Dhammic hydraulic orology will allow us to address two questions liable to arise when confronted with such an optimistic panorama: How can there be such positivism in the face of dukkha? And what’s this about happiness leading to concentration? By directly addressing these questions, I hope to give both a realistic and attractive contoured map of our wellbeing landscape, to help foster a curiosity that wants to experience the peak’s first showers.

The proposition that “For one engaging in radical awareness, a sense of wellbeing arises,” is conveyed in Pāli with just three words: “Yoniso-manasikaroto pāmojjaṃ jāyati.” This simplicity, however, can easily elicit frustration: What is this ‘radical awareness’? How does one do it? And where is this “wellbeing”? Though referring to the same sentence, each of these questions will require its own analysis. To carry out this inquiry, I will examine these central questions through linguistic dissection of the Pāli, intertextual study, intratextual comparison, and personal experience. It is hoped that this multi-modal apparatus will enable a fuller understanding of the practicable implications of this vital teaching. Through such deep reading and investigation, a better understanding of the early mechanisms behind this optimistic causality can be discerned.

II. The Mountain Itself: What about Dukkha?

Before immersing ourselves in the pleasing waters of the wellbeing cascade and its path of sukha, an immediate question faces us: What exactly is the mountain beneath our feet? In this central metaphor, what does the mountain represent? Is it saṃsāra—the endless round of rebirths? Is it the body? Or, is it something else? Each of these propositions seems to hold some truth and warrants further investigation.

The mountain representing the whole of saṃsāra is compelling. In a Buddhist worldview, this single human life is not the whole of the story. Rather, based on the momentum of their own craving, all beings transmigrate through multiple lives in multiple realms—in heavens and hells, and as animals, ghosts, titans, and humans. And this process viciously repeats itself until one learns how to desist from fueling the process through the inner work of self-restraint. At Itivuttaka 24, the Buddha explicitly compares the duration of saṃsāra to a mountain:

If a single person were to run around and wander in saṃsāra for an eon, their chain of bones—if it could be amassed, collected, and not destroyed—would amount to a mound of bones, a heap of bones that would be as huge as this Vepulla Mountain. (Itivuttaka 24)

In this graphic simile, the Buddha uses his all-encompassing vision to elaborate on the plight of existence. Through his development of the “divine eye” which can see other realms of being, the Buddha is saying that “if beings knew as I know,” they would see that their karmic baggage is immense (Itivuttaka 26). So, saṃsāra is indeed a mountain of sorts. But it seems the image’s implications can be drawn out further.

Perhaps this human body is the mountain being rained upon? One of the Buddha’s primary designations for the body was, after all, the concretely terrestrial term khandha, meaning simply a “heap” or “mass.” Indeed, the Pāli term khandha appears in many mundane, compound words with explicitly physical denotations, such as “a mass of fire,” “a body of water,” and “a heap of logs.” By choosing this word to describe the body, the Buddha was making the point that, stripped of all the significance we give it, the human body is, just like the mountain in our simile, just a temporary grouping together of physical elements. Whether one is discussing Mount Everest or the molehill that is “this fathom-long body,” the physics of both are the same (Aṅguttara Nikāya 4.45). The Buddha made this point explicit in a teaching to his young son, Rāhula, when he proclaimed “Truly, the internal earth element and the external earth element are both simply the earth element” (Majjhima Nikāya 62).

Having explored how both saṃsāra and the body are mountain-like in their own ways, it is a useful exercise to see if there is a common denominator between the two: might there be some even more fundamental referent being alluded to? In searching for such a shared underlying phenomenon, one needn’t look far, either in the Buddhist Canon or in one’s own life: any time we look, the truth of dukkha is ready to be seen. Truly, dukkha is foundational to both saṃsāra and to our experience of having a body. It is part and parcel both with saṃsāra and with its transcendence. As for the relationship between the human body and dukkha, one needn’t even look to scripture: just sit still for thirty seconds longer than you’re used to and … there it is.

Although our central metaphor does not explicitly state that the mountain itself represents dukkha, this seems a fair elaboration. In the highly memorable “Discourse on the Simile of the Mountain,” the Buddha makes precisely this connection, comparing the dukkha of bodily aging, sickness, and death to four “great mountain[s], high as the sky, coming along crushing all beings in [their] path” (Saṃyutta Nikāya 3.25). What the wellbeing cascade metaphor then appears to provide is a downpour of psychological sustenance, a percolating enrichment and revitalization of parched rockface. But care should be taken to not rush past this truth of the mountain’s pre-watered aridness.

The Buddha famously declared on several occasions, “Formerly and now, I teach just dukkha and the cessation of dukkha,” or, as the working interpretation in this paper would have it, the mountain and the cascade (e.g., Saṃyutta Nikāya 22.86). While our central watery metaphor speaks largely in the language of the “cessation of dukkha,” in no way does it reject or deny the truth that “There is dukkha” (Saṃyutta Nikāya 45.8). If a weary and heat-stricken mountaineer is seeking a cool pool, they can’t just imagine it into existence but must walk the ground beneath their feet to get there. Accepting that the mountain itself is, at least in part, the type of unavoidable dukkha inherent to being human, the mental mountaineer who follows the map of the wellbeing cascade will never be surprised: dukkha is to be as expected.

Having come to this understanding, however, it must be acknowledged that, if one is suffering deeply, it can be hard to hear talk about happiness. For one who only sees rocks, talk of the sea can seem insane or at least unkind. This dissonance is perhaps akin to the principle according to which the Buddha suggests:

Talk on faith is wrongly addressed to someone who lacks faith. When talk on faith is being spoken, a person who lacks faith becomes irritated, agitated, angry, and stubborn; and they show their anger, hatred, and discontent. Why? Because they do not perceive that faith in themself, and they do not gain joy and a sense of wellbeing (pāmojja) because of it. [So too with “talk on virtue, learning, generosity, and discernment” for people who lack those.] (Aṅguttara Nikāya 5.157)

In like manner, when one is suffering, talk about happiness can be difficult to hear. On the level of words, the salve of sukha can seem an irritant; sweet sukha tonic can seem astringent. It seems a broadly shared experience that, even for Buddhists seeking happiness and wanting to live by their Teacher’s instructions, a personal experience of this wellbeing cascade can feel distant, and the applied meaning of its various clauses can remain enigmatic and unapproachable. Finding one’s head shoved ten inches deep in the dirt of the mountain trail, one looks around and sees only “a mass of darkness.”

But is dirt and darkness really all there is? This is not a trivial question: for one mired in suffering, the answer that seems most viscerally true might be “yes!” This being the case, the Buddha is wise to have begun his metaphor with the mountain, and to have begun his teaching with the First Noble Truth of dukkha. Indeed, how can one deny either? Dark is the state of things at night; rocky is the nature of the mountain. The Buddha, however, did not stop there, but further proclaimed the cause of dukkha (how craving is what faceplanted one in the first place), the end of dukkha (the great ocean at the end of the wellbeing cascade), and the path leading to the cessation of dukkha (of which the wellbeing cascade itself is one manifestation). While there may be other paths to transcending suffering that don’t involve the nourishment of wellbeing, the “nine habits of mind that are exceptionally helpful” are helpful precisely because they speak so directly to the natural desire to be happy (Dīgha Nikāya 34). This is significant, because the path to liberation may be a long one, and to sustain such a journey, I believe, one needs positive affective encouragement and nourishment along the way.

III. The Fifth Pool: A Brief Dip in Sukha and Samādhi

Our next step, before looking up to the heart founts of radical awareness and wellbeing at the mountain’s peak, will be to examine an important turning point midway down the mountain. Specifically, to the cleft where happiness (sukha) overflows into concentration (samādhi). This is a critical transition—personally, philosophically, and pragmatically—as it brings up a crucial question: How is the path supposed to feel?

Although the word “sukha” can be translated in many ways—happiness, pleasure, bliss, ease, joy—at its most basic, it is definitionally a feeling (vedanā), namely, the polar opposite of dukkha (Dīgha Nikāya 34). In the wake of the mountain of dukkha just discussed above, how can these seemingly opposing affects be reconciled? This is not merely an idle speculation but can be the beating heart of a practitioner’s life. Though a paper can only go so far, these issues will be addressed through examining two vital quandaries: What is sukha? And, critically, is it the cause or the result of practice?

III.1 Happiness as Path? Sounds Great! Why Question It at All?

For newcomers to Buddhism, it might be surprising to learn that conceiving of the Dhamma as a path of happiness is not necessarily the lived experience of many “serious meditators.” For many a strident yogi, the path is a path to happiness. For these, formal sitting meditation is perceived to be the whole of Buddhist practice, and is something—unpleasant on multiple levels—that must but be teeth-grittingly endured in order to, one day, experience the true sukha of liberation. Though our wellbeing cascade explicitly states in step five that, “For one who is happy, the heart becomes concentrated,” this translation depends on a controversial assumption. Indeed, it must be admitted that the straightforward translation of sukha as “happiness” here, rather than as the more common rendering “pleasure” (or even more explicitly as “non-sensual pleasure”) masks a contentious premise.

To summarize this discrepancy of translation and its underlying presumptions, I turn to an oft-repeated challenge made by my teacher Luang Por Pasanno:

We see that happiness brings about samādhi, whereas usually, we approach it the other way around. We often think, “If only I could get my meditation [samādhi] together, then I would be happy,” whereas it should be: “How do I gain true happiness so that my heart could be at ease?” It is a very important truth that the Buddha points to in this sequence of shades of happiness culminating in samādhi. (Pasanno 2001: 20)

The “sequence of shades of happiness culminating in samādhi” that he speaks of is precisely our wellbeing cascade, and this interpretation is, as Luang Por Pasanno notes, not at all normative in all Buddhist practice circles. Many “practice traditions,” especially those popular in the West, presume that “happiness” is more rightly conceived of as a by-product of concentration rather than a cause for its arising. These are the same circles that would prefer to translate “sukha” in its pre-concentration form as “pleasure,” suggesting that its import is limited to the spiritual, non-worldly pleasure (nirāmisa samādhi-sukha) that is an absorption factor (jhānaṅga). To translate “sukha” as “happiness” here would, they feel, cheapen the Buddha’s more exalted intention. There is undeniable truth to this reading: the goal of practice, Nibbāna, is, after all, acknowledged to be the “highest happiness” (Dhammapada 203—204). Is it possible, however, that Luang Por Pasanno’s upturning of this popular narrative might also be a valid interpretation?

Is this view linguistically sound and doctrinally supportable? The investigation that follows will examine these important questions. At the outset, though, I need to admit my own bias.

III.2 Authorial Perspective of Sukha

Whatever the textual investigation that follows turns up, it seems legitimate to insert at least some measure of personal perspective to address this question of whether there is happiness along the path or merely at its end. So, what is my authorial perspective on this? And why do I believe it?

With measured examination, I must admit that it is indeed my own opinion and faith, and, to some acknowledgedly limited degree, also my lived experience that happiness isn’t just a surprise and wholly different byproduct of an unhappy path, but can be of a piece with the path itself. In the language of our mountain, it is my belief and feeling that the cascade affords a measure of coolness not just at its end—the great ocean—but also in the many and various pools along the way. This faith is based both on “the voice of another,” namely my teacher Luang Por Pasanno’s, and on my own attempts at “radical awareness” (yoniso-manasikāra), that is, the cloud in our central metaphor and the subject of a later section in this paper.

While anecdotal evidence can be suspect, it gains weight and legitimacy in two ways: when the anecdotes are tested over time; and when the number of anecdotes (the population size) increases. Luang Por Pasanno’s perspective that, as quoted above, “happiness brings about samādhi,” is informed by his five-decades-long dedication to monastic life. It is further supported by his thoroughgoing observations of the hundreds of monastics who have trained under his guidance throughout his forty years as an abbot and guiding elder. Having seen scores of extremely sincere yet otherwise imbalanced meditators disrobe over the years, it is his experience that a spiritual life lived without a sense of wellbeing is unsustainable. Under his guidance, rather, a disciple is trained in “the fundamentals of the holy life,” a regime that involves performing devotional practices, keeping precepts, service to the Saṅgha, scriptural study, and deep and meaningful friendships alongside formal sitting meditation. Such fundamental practices, he has observed, provide the joyful “water of the heart” which can lubricate an otherwise dry practice overly burdened by dukkha. And sustained and nourished by such basic waters, he repeatedly reports, the mind can become “easily concentrated” (Pasanno 2001 40).

Luang Por Pasanno is admittedly my teacher and by quoting him as a source, I am liable to be accused of committing a logically questionable “appeal to authority” (UNC-Chapel Hill Writing Center). While there is no way around this accusation for someone who does not even believe in spiritual authority, my faith in Luang Por Pasanno’s account is bolstered by criteria for judging another person’s trustworthiness given by the Buddha himself. These criteria are presented thus:

It is through living together that someone’s virtue may be discerned … through interaction that someone’s purity may be discerned … through adversity that someone’s resilience may be discerned … [and] through conversation that someone’s wisdom may be discerned. And [all] this, over a long while by someone observant and wise, not just over a short while by someone unobservant and unwise. (Aṅguttara Nikāya 4.192)

While I can’t vouch for the level of my observantness or wisdom, I have lived intimately with, interacted closely with, and conversed extensively with Luang Por Pasanno for well over a decade and, on multiple occasions, have witnessed him handle difficult situations with grit and grace. All this to say, I am content to trust—at least as a working hypothesis—his perspective here that one needn’t wait till samādhi coalesces to experience happiness. One can, his interpretation of the wellbeing cascade illustrates, seed and condition happiness further upstream with wholesome and blameless conduct.

In addition to my confidence in Luang Por Pasanno’s knowledge of the wellbeing cascade’s terrain, I have observed a measure of the profundity and truth of this interpretation myself. Both in my own experience and as I have witnessed in the practices of my peer monastic postulants, a one-legged approach of “meditate, meditate, meditate” does not work in and of itself. For my first several years of monastic life, I took meditation as my primary vehicle for practice and consciously shunned other supports such as service, study, and kindness. Feeling myself to be a “serious meditator” I looked down on the cheerful volunteers making my meals and on scholar monks who didn’t spend any time on the cushion. To sum up, it was an isolated and depressing time in my life. I had swallowed the rhetoric of the primacy of meditation over all else, and gotten drunk on that conceit. While moments of ease and kammaṭṭhāna-sukha did arise, they were not long-lasting or reliable, as they were always susceptible to being intruded upon by other people or unexpected circumstance.

Coming from a meditation-then-happiness approach, I became hard to live with. I was valuing an ideal of some future happiness (especially jhāna or Enlightenment) to be hard-won through hours and days on the cushion over the happiness of possible friendships to be gained by being a friendly and generous person. The sit-first-then-sukha-later belief was making me antisocial and selfish. After being passed over and denied ordination at one monastery, and then having my ordination delayed at another, I was finally permitted to take full ordination with Luang Por Pasanno as my preceptor. By that time, I had been living at monasteries for three years and had been surrounded by abundant evidence, both subtle and explicit, that there was another, happiness-now-and-happiness-later approach to a spiritual life that was also possible. Though I can’t say that I am now never selfish, being allowed to ordain did provoke a sense of gratitude that subtly yet effectively served to break the fault-finding conceit upon which my meditation-then-sukha mindset was founded.

There is a common phrase found in the Pāli Canon spoken in praise of the Dhamma, that it is “beautiful in the beginning, beautiful in the middle, and beautiful in the end” (e.g., Dīgha Nikāya 2). In my experience, interpreting this phrase to mean “entailing happiness in the beginning, entailing happiness in the middle, and entailing happiness in the end,” is both possible and beautiful. A life lived inclining towards these “timeless” and “apparent-here-and-now” levels of wellbeing is a spiritual life that seems attractive and sustainable.

To have the psychological wherewithal to be able to observe the “first arrow” of inevitable, bodily pain (kāyika-dukkha) without “striking oneself immediately afterward with a second arrow” of avoidable, mental anguish (cetasika-dukkha), it is my experience that one needs at least some measure of the buoyancy that comes from a happy and unstuck (visaññutta) mind (Saṃyutta Nikāya 36.6). Though, in many ways, each one of the wellbeing cascade’s various plateaus serves this function, it is in the naturally ensuing overflowing from the fourth to the fifth pools that happiness/pleasure (sukha) is explicitly named. It is also here that the mental stability of concentration (samādhi)—profoundly and definitionally infused with wellbeing—is first mentioned.

III.3 The Chicken and Egg of Sukha and Samādhi

We have surveyed personal experience, but what do the texts say about the relationship between these states? According to the Pāli Canon, is the Buddhist path one of teeth-gritting endurance and staring at the breath until samādhi is accessed? Is happiness attained only thereafter—a linear samādhi-to-sukha affair? Or is it the case that, in the memorable words of Luang Por Pasanno, “the happy mind is easily concentrated”—a serial sukha-to-samādhi situation (Pasanno 2001: 20)? Or, is the causality more complex—a …-sukha-to-samādhi-to-sukha-… feedback loop? To undercut these issues before they multiply unnecessarily, it may be helpful to turn to a discourse that makes a critical distinction between different types of sukha.

In the “Discourse on the Analysis of Non-Conflict,” the Buddha matter-of-factly enjoins, “One should know how to define sukha. And knowing this, one should devote oneself to internal sukha” (Majjhima Nikāya 139). He then makes a distinction between: 1) sensual-sukha which is “not to be associated with, developed, or made much of, but is rather to be feared”; and 2) the internal sukha of letting go which “one should devote oneself to … [and which] is to be associated with, developed, made much of, and is not to be feared.” He defines sensual-sukha as being “the five cords of sensuality”—sights, sounds, aromas, tastes, and touches that are “wished for, desirable, agreeable, likable, connected with sensual desire and provocative of lust.” And he rounds out this description bluntly, not mincing words as he calls them alternatively, “excretory-sukha, unenlightened-sukha, and ignoble-sukha.” This is the sukha that practitioners who balk at the idea of sukha preceding concentration rightly recoil from. Indeed, this is the mundane, saṃsāric “happiness” of beautiful scenes, alluring music, fragrant scents, delectable cuisine, and sensuous contacts that is all too prone to eliciting intoxication, obsession, and addiction.

Fortunately, the Buddha also declared that there is a second type of sukha—the sukha of letting go. He begins his discussion of this form of sukha by defining it with the standard formula for the four jhāna absorptions, the elaboration of which begins with “disengaging from sensuality and disengaging from unwholesome states”—a reference to intentionally and skillfully turning away from that first type of sukha, sensual-sukha (Majjhima Nikāya 139). He then goes on to alternately call this sukha of letting go, “the sukha of seclusion, the sukha of peace, and the sukha of awakening.” Although he mentions the four jhānas by name as being exemplary manifestations of this form of sukha, a reasonable, commonsense case can be made that the happinesses of generosity, virtue, sense-restraint, and other wholesome Dhammas can similarly be subsumed under this umbrella of sukha that is allowable and laudable. Indeed, elsewhere he commends such forms of sukha as being “internally blameless sukha … [and] untainted sukha” (e.g., Majjhima Nikāya 27, 38, 51, etc.). As mentioned earlier, these sukhas are those expedient ones which can rightly be counted as “beautiful in the beginning” and “beautiful in the middle” (e.g., Dīgha Nikāya 2).

To gain a fuller sense of the scope of this praise-worthy sukha of letting go, it is helpful to turn to a very short but exceedingly pithy Discourse in the Aṅguttara Nikāya. Though in some editions of the canon, the discourse is not even given its own name, it succeeds in a few potent lines to encapsulate, for me, the essence of what “faith” (saddhā) entails in Theravāda Buddhism. It states:

Abandon the unwholesome. It is possible to abandon the unwholesome … Because abandoning the unwholesome leads to benefit and sukha, I say, “Abandon the unwholesome.” Cultivate the wholesome. It is possible to cultivate the wholesome … Because cultivating the wholesome leads to benefit and sukha, I say, “Cultivate the wholesome.” (Aṅguttara Nikāya 2.19)

In essence, this is the foundational belief of the Buddha’s path. Further, it is the base upon which the path can be framed as a training in the skill of sukha. But one might ask: Does the reverse logic of the above work here as well? Is it the case that if the Buddha says to cultivate something, then that something is definitionally wholesome? And if something is wholesome, does this further suggest that it leads to benefit and sukha? The Buddha expressly confirms this logic in relation to virtue (keeping the five precepts) and faith (properly placed in the Triple Gem) at Aṇguttara 8.39 and 4.52 respectively.

With this principle in mind, it seems safe to hold that each of the waterbodies that hover above, pool upon, and flow down through our mental mountainscape—including all those that precede this specific fifth reservoir where sukha touches samādhi (namely: radical awareness, a sense of wellbeing, joy, and bodily relaxation)—can similarly be encompassed by this praiseworthy sukha of letting go. It is these various and expansive, lived embodiments of sukha-as-happiness, I believe, that Luang Por Pasanno was pointing to as being legitimate, pure, and faultless concentration-preceding states of happiness.

How can the coolness of this fifth pool be summed up? As has been shown, it is the reservoir where sukha mixes with and overflows into samādhi. But such simplicity of expression belies a more complex reality. For some practitioners, conditions have come together such that the path is felt primarily as dukkha. Such people might be likened to mountaineers on the dry side of the mountain; they are diligently seeking the samādhi pool and the great ocean of liberation, but feel themselves far from them. For other practitioners, sukha, in its various course and subtle forms, is predominate. These are the hikers, sometimes walking in harmonious groups, who’ve been following the wellbeing cascade down the mountain. But what was the weather at the mountain’s peak? For the remainder of this paper we will finally address this question of the water’s source and turn to the sky, to the cloud of radical awareness that the Buddha said was the inception of our mountain’s watery sustenance.

IV. Before the First Pool: The Clouds of Radical Awareness (Yoniso-manasikāra)

Having touched upon the sukha and samādhi currents whirling within the fifth pool of the wellbeing cascade, let us return upstream to the initial precipitation whose ground fall fed it, that is, yoniso-manasikāra or radical awareness. This radical awareness is likened to “a raincloud shower[ing] down big, fat droplets of water on top of a mountain” (Saṃyutta Nikāya 12.23). The subsequent pools of rainwater flowing down the mountain are metaphorical representations of the “nine habits of mind that are of great benefit,” namely: 1) wellbeing (pāmojja), 2) joy (pīti), 3) bodily relaxation, 4) happiness/pleasure (sukha), 5) concentration (samādhi), 6) seeing in accordance with reality, 7) being untroubled (nibbinda), 8) utter coolness (virāga), and 9) true liberation (vimutti) (Dīgha Nikāya 34). But what is habit number zero, the cloud whose “big, fat droplets” will rain down and feed into the vast ocean of true liberation?

To get an initial taste of this refreshing rainwater, let us first sip at its etymology and sup its chosen translation. For starters, it is essential to note that the Pāli word yoniso-manasikāra is a compound whose individual parts—yoniso and manasikāra—each have their own rich meanings. Be that as it may, the combined meaning of these words when joined is both fit to stand on its own and stronger than the sum of its parts. Here, it is useful to examine each component’s meaning and thereafter explore their combined power.

IV. 1 Yoniso is Radical

As the Pāli-English Dictionary and the Concise Pāli-English Dictionary note, the isolated and therefore enigmatic word yoniso conveys meanings of thoroughly, wisely, properly, prudently, and carefully, (“yoniso” Rhys Davids, Buddhadatta). Each of these “ly”-suffixed English adverbs has its elegance, and each reveals useful nuances of the original Pāli. For example, there are contexts where yoniso modifies a type of comprehensive “striving” (padahaṃ) that results in demolishing all suffering in which the modifier “thoroughly” would seem most appropriate (e.g., Itivuttaka 16, Anālayo 2009). In a verse from the Elder Gayākassapa, yoniso in its sense of “wisely,” modifies a manner of reflecting on teachings to make the best use of them (Theragāthā 5.7). And in the verses repeated several dozen times in the canon, practitioners are advised to “carefully (yoniso) consider their use of clothing … food … shelter … and medicine” (e.g., Majjhimā Nikāya 2, 39; Saṃyutta Nikāya 35.120). In these instances, the type of consideration being suggested is a circumspect, careful, and prudent one with distinct variations of attention being advised for each requisite, that is, the manner in which one should “carefully consider” their use of clothing differs from how they should consider their use of food, et cetera.

While each of these implied, adverbial translations are valid, there is another important aspect of yoniso that can helpfully be drawn out, namely, its most literal meaning: “from [or] to the womb (yoni)” or “down to its origin/source/foundation” (“yoni” Rhys Davids). Such a distinct, vivid, and evocative reference begs many questions about the scope of this term in the original Pāli. To determine this range of meaning, I have turned to the fascinating “compound family” resource accessible through the comprehensive Pāli dictionary/database called the Digital Pāli Dictionary. Through using this tool, it can be seen that the Pāli (and Sanskrit) word yoni is used in three main contexts. First, it is used to refer to biological uteri—of humans (manussa-yoni), of animals (tiracchāna-yoni), and of other mythological creatures (e.g., dragons—nāga-yoni). Secondly, yoni can refer to broader conceptions of gestation such as oviparous (egg-based—aṇḍaja-yoni) and parthenogenetic (moisture-based asexual—saṃsedaja-yoni) reproduction (“Parthenogenesis” Merriam-Webster). And finally, yoni appears in a doctrinally significant metaphorical elaboration of the implications of intentional action (Pāli: kamma, Sanskrit: karma) that states “I am … born from action” or, more precisely, “I am … the womb of action (kamma-yoni)” (Aṅguttara Nikāya 5.57, 10.48). Thus it can be seen that the word yoni is replete with meaning—biological, reproductive, and metaphorical.

Surveying this throng of fecund metaphor, grammar, and implication, I have chosen to respond to the question of yoniso’s translation with the unconventional, yet both precise and poetic adjective “radical,” whose essential meaning is “going to the origin … ground,” “of or having roots” (“Radical” Etymonline). In addition to this “root/origin” meaning, the “unconventional” and even “extreme” nuances of the English word “radical” are also shared with the Pāli. Indeed, in its role as a “factor for (attaining) Stream-Entry,” awareness that is yoniso is a unique prerequisite for that rare and remarkable attainment (Dīgha Nikāya 33); if yoniso-attention was the psychological norm, Stream-Entry and higher attainments would not be so “rare in the world” (Aṅguttara Nikāya 6.96).

Though a working definition for yoniso as “radical” has been established, what of the second part of the compound? What are the implications and meanings of “manasikāra”?

IV.2 Manasikāra: What the Mind Does

Manasi-kāra, itself a type of compound, is typically rendered as “attention,” and points to some form of action (-kāra) of the mind (manas). As a mental function in itself, manasikāra is one of five aspects of mentality (nāma), and is classed in the Theravāda Abhidhamma as being a “mental factor that is common to all types of consciousness.” Though nothing permanent in Buddhism, it is an aspect of the mind that constantly re-occurs and incessantly re-arises, yet in ever-changing forms (Dhammapada 277). Indeed, it is stated plainly in the Aṅguttara Nikāya that “all phenomena have their origin in manasikāra” (8.83, 10.58). Such phenomena crucially include not only neutral states of cognition like thought and impulse, but also such ethically-weighted and karmically-charged mind states as greed, anger, conceit, and doubt. In choosing a translation for this effectively ever-present manasikāra mental movement, it thus makes sense to ask: what English word or words best conveys such broad implications?

Most translators (Bodhi, Ṭhānissaro, Horner, Sujāto) have chosen the accurate dictionary-attested “attention.” But, to me, “attention” feels rather limited. Might there be a more expansive yet still accurate translation?

What about manasikāra as “awareness”? Such a translation balances considerations both of the original Pāli’s scope and its flavor and savor (“Yoniso Manasikāra – the Many Faces of Wise Reflection”). Such a word choice also gains support from modern psychological literature that delineates a precursory relationship between “awareness” and “attention” concluding that the former precedes the latter. For example, studies in which subjects are presented with a subliminal visual cue demonstrate how, though consciously aware of visual datum as a whole, attention and recognition do not necessarily always follow (Hsieh 1). Furthermore, to me, “awareness” feels more spacious than “attention,” and thus more aptly suggests the infinite sky within which the rainclouds of our central metaphor might appear.

With “awareness” as a functional translation with its own merits, the question then arises of what one does with said “awareness”? How can the form of the word that is found in the phraseology of the wellbeing cascade be translated in a way that is uplifting, accurate, and compelling? The scope of the meanings of the verbal root √kṛ from which the second part of manasikāra derives runs from the plain and prosaic (“to do, make, cause”), to the industrial (“to manufacture, work at, construct”), to the niche (“to procure, impose”) (Williams; Rhys Davids). None of these, however, seems a good match for the nuanced mental work being described here. How about, instead, to “engage in”? This translation is poetic, accurate, and encouraging. To me, it suggests an active, positive impulse (Right Effort) of a balanced mind (Right Mindfulness) sustained with interest over time (Right Concentration). So, there it is: one engages awareness.

IV. 3 Yoniso-manasikāra: A Billowing and Full Cloud

Having touched on the individual implications of its component parts in the preceding sections, I have come to the following translation for the first word of our focal sentence: “For one engaging in radical awareness …” Our helpful mind habit number zero now has a name and vector—“radical awareness,” awareness that “goes to the source”—and our interaction with this virtue now has an operative relational signifier—“for one engaging.” But though this translation is straightforward enough on paper, the term’s significance is perhaps still vague. The metaphorical cloud of yoniso-manasikāra may still appear as a hazy, gray fog rather than as a clear-edged and cumulous mass; the movement of karoto (the one engaging it) may still be indistinct. What is the “source/womb (yoni)” that one engages with in radical awareness? What is the textual shape and scriptural context for it? And how does one actually mentally engage with it—i.e., seed the clouds—so as to engender the promised rains and pools of wellbeing?

The first line of the Dhammapada gives us a clue as to what “source” yoniso-manasikāra might be attuning its awareness to. Its four, succinct Pāli words boldly purport, “All phenomena (dhammā) have their forerunner in the mind (mano). Mind is their chief. They are mind-made” (Dhammapada 1). Thus, the source of everything, that from which all phenomena are born, is the mind or heart. So with this textual infusion of meaning, yoniso-manasikāra can be understood as an inverted awareness—a movement (kāra) of the mind (manas) that goes to/comes from the mind-as-source (yoni). This U-turning of attention alluded to both in this first Dhammapada verse and in the psychodynamics of radical awareness is comparable to the Third Foundation of Mindfulness, Observation of Mind (cittānupassanā), which is succinctly defined as follows: “One abides observing mind in the mind—ardent, alert, and mindful—letting go of attraction and dissatisfaction with the world” (Dīgha Nikāya 22). Thus, we have three iterations, using different terminology and found in disparate contexts, of mind-knowing-mind practice: (1) seeing that “All phenomena have their forerunner in the mind”; (2) engaging in radical awareness; and (3) Observation of the Mind. In each instance, the vector of the mind’s attention returns, in the locative case, back to the mind itself. Rather than dispersing its energy out through any of the senses as is the norm for most people most of the time, the mind instead turns and rests in itself.

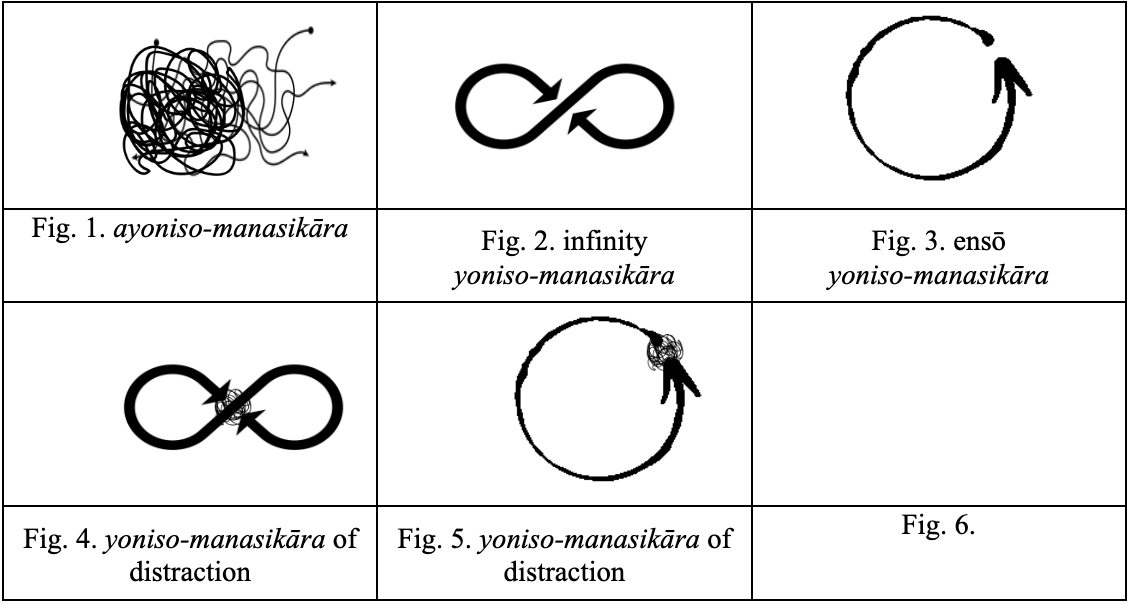

It will be helpful here to give a visual metaphor comparing the difference between the habitual cognitive dissipation (the negated “a-yoniso-manasikāra” that is fully obsessed with “attraction and dissatisfaction with the world”) and the reflective, self-contented, doesn’t-need-to-go-out mental stillness that is being delineated in this study. While externally-scattered awareness can be imagined as a knotty and tangled scribble (figure 1, below), the healthy inversions of sentience being suggested by the Buddha are like a self-contained, infinity symbol (figure 2) or an elegant Japanese ensō brushstroke (figure 3). The emphasis with these latter infinite and ensō graphic comparisons is not necessarily their perfection, but rather their reflexivity.

As the extended description of the Third Foundation of Mindfulness illustrates, Observation of Mind involves not only knowing “an undeluded mind as undeluded … an unsurpassed mind as unsurpassed … [or] a liberated mind as liberated” but can entail witnessing “a lustful mind as lustful … a hating mind as hating … a distracted mind as distracted … [and] an unliberated mind as unliberated” (Dīgha Nikāya 22). Just as a transparent, digital PNG image of an infinity sign (figure 4) or an ensō (figure 5) can be transposed over the top of a messy, tangled scrawl simply and seamlessly without damaging those more foregrounded layers, so too can mind know mind by foregrounding yoniso-manasikāra. From a higher peak of awareness, the mind’s-objects can be seen and not feared. And from this grander vista, it is not too difficult to look up and see the whole of empty space (figure 6).

Figures of Awareness:

Though this simile of transporting the mind to lofty heights overlooking troubled valleys is striking and catches some sense of the flavor of radical awareness, the signified shift of view need not necessarily be the psychic equivalent of being “beamed up” vertically. Turning the mind around in this way needn’t entail experiencing heightened or altered states of meditative absorption. Rather, the reflectional shift of consciousness being alluded to is a more subtle, yet still profound, intentional movement from merely and compulsively adverting to external gratification to remaining and resting content inwardly. This perceptual revolution (i.e., yoniso-manasikāra) entails using the mind’s eye to glance back at its own centerless center rather than to stare hungrily outwards.

This practice of radical awareness is captured beautifully by two, twentieth-century Thai meditative virtuosos, Luang Pu Dune and Upāsikā Kee Nanayon. Luang Pu Dune speaks to this mental turnaround by reformulating the Four Noble Truths as follows:

The mind sent outside is the origination of suffering. The result of the mind sent outside is suffering. The mind seeing the mind is the path. The result of the mind seeing the mind is the cessation of suffering. (Dune)

By switching the traditional ordering of the Noble Truths and using the active vocabulary of “send[ing] outside” (the function of the āsavas) to denote the problem, and “mind seeing the mind” (the Third Noble Truth or yoniso-manasikāra) to denote the solution, Luang Pu Dune clears the path and makes it more walkable.

Pointing to an awareness engaged in exactly this non-valence, Upāsikā Kee Nanayon describes it in verse:

An inward-staying

unentangled knowing,

all outward-going knowing

cast aside. (Nanayon)

In the first two lines of this verse, Upāsikā Kee beautifully describes a living form of radical awareness as “unentangled knowing.” Though this translation chooses the word “knowing” rather than “awareness,” it seems to me to be suggesting the same expansive application of consciousness. Lines three and four of the poem—“all outward-going knowing cast aside”—reflect back to the enjoinder in the Observation of Mind practice mentioned above, that is, “letting go of attraction and dissatisfaction with the world” (Dīgha Nikāya 22).

In the language of the Pāli Canon, this is the psychic transition from “outflowing” (āsavā) to being “devoted to internal serenity of mind” (ajjhattaṃ cetosamathamanuyutta). Yoniso-manasikāra is the antidote to the mind’s propensity to flow out with the āsavas, or the effluent, psychological effluxes of sensuality, egoic-becoming, ignorance, and opinions that, in the whimsical words of the 1921 Pāli-English Dictionary: “intoxicate the mind … bemuddle it, befoozle it, so that it cannot rise to higher things” (“āsava” Rhys Davids). Every moment spent engaging in radical awareness is a moment not spent outflowing; and every moment not spent outflowing is a moment spent on the Eightfold Path; and every step taken on that path is a step closer to liberation.

True to this interpretation, the Buddha proclaims in the “Discourse on All the Outflows” that “For one engaging in radical awareness (yoniso manasikaroto) unarisen outflows do not arise and arisen outflows are abandoned” (Majjhima Nikāya 2). And just a few pages later in the “If One Might Wish Discourse” the Buddha further praises this reappraisal of our attentional vector stating:

If one might wish “With the destruction of the outflows, having entered upon and realized with true insight for myself here and now the liberation by wisdom and liberation of mind that is outflow-free, may I simply abide” Let one … be devoted to internal serenity of mind. (Majjhima Nikāya 6)

In these passages and with the introduction of the concept of “outflowing” (āsavā), we are encountering a different hydraulic dynamic than that of our wellbeing cascade. Indeed, for the wellbeing cascade to even begin its pooling process, one must first (and then repeatedly) stop allowing awareness to flow out by way of the always-unwholesome outflows. To draw out this analogy, it is as if our mind-cloud has two capacities: it can either supply to the mountain top the refreshing showers that will instigate the wellbeing cascade; or it can dump unto the valley a sooted and miasmic deluge. The former hydrodynamics are those of yoniso-manasikāra; the latter are those of the āsavas.

V. The First Pool: Radical Awareness Groundfalls to Wellbeing (Pāmojja)

Having stemmed the āsavas, and returned the mind to its yoni-source through radical awareness, we now begin to feel the nourishing first drops of pāmojja. To get a preliminary feel for this heart state, it is fruitful to wonder, “What is its meaning in Pāli?”

Various Pāli-English dictionaries define pāmojja as “delight,” “joy,” or “happiness” (Rhys Davids; Buddhadatta). But for pāmojja as we find it in the wellbeing cascade, its translation needs to take account of its ordering in relation to other pools along the mountainside. In the progression, pāmojja comes before joy (pīti) and happiness (sukha), and thus needs an English translation that is not as intense as joy, but rather more fundamental and precursory. It is my feeling that “wellbeing” fits this bill nicely. Further, in addition to encountering pāmojja preceded by radical awareness, it is also found following in the wake of many other various wholesome qualities. An utterly partial list of such starting points includes: unwavering confidence in the Triple Gem (Saṃyutta Nikāya 55.40); recollection of one’s own generosity (Aṅguttara Nikāya 6.10, 11.12); virtue and non-remorse (Aṅguttara Nikāya 11.1); reflecting on one’s own honesty, celibacy, asceticism, and learning (Majjhima Nikāya 99); and abandoning the mental hindrances (Dīgha Nikāya 2, 9, 10, 13).

Given the effusive nature of the positive self-esteem naturally engendered by such habits, I feel there is a case to be made for appending “a sense of” to the plain “wellbeing” to indicate a more pervasive, seasoned, and encompassing resonant tenor to the understanding of this beautiful dhamma. On top of this, “wellbeing” well-conveys the appropriate sense of depth, durability, and maturity that the positive affect resulting from the various wholesome acts just mentioned bestows. That is, it is a shared religious experience that the psychological satisfaction that comes from being generous, keeping precepts, and training the mind is not a random or volatile “zest” or “exuberance.” Rather, pāmojja is a more meaningful and enduring “sense of wellbeing” born from healthy habits and issuing in joy. To instantiate this, the Buddha gives the following vivid metaphors for what it feels like to train the mind in the ways described above:

When a monastic reflects and see that these five hindrances are abandoned in themselves, they view this as being like freedom from debt, a state of health, release from prison, freedom from slavery, and like a land of refuge. Reflecting on their own abandoning of these five hindrances, as sense of wellbeing arises. Having a sense of wellbeing, joy arises.

Far from being a fleeting sparkle of positivity, pāmojja is here likened to the peace resulting from some of the biggest reliefs possible in the human experience.

Having kept so strictly to the script of the Pāli Canon, and having so dutifully adhered to the standards of academic writing so far, I will now ask, in these last pages, to allude to my own experience of pāmojja through a lively dive into its etymology. Given the inherently emotional and “to-be-experienced-individually” nature of pāmojja, such a personal account seems appropriate (e.g., Dīgha Nikāya 16).

Even if you have never heard the word pāmojja before, just its sound is accurately expressive of its connotations as I experience them. Its initial, English bilabial plosive “p” pleasantly and pleasurably properly provides peaceful pep and playful pazazz to people’s practice. Its Pāli prefix “pa-” has the following implications: forward movement (as in pabbajja—going forth); intensification (as in pabhāsa and pajjala—radiance, blazes); and onwardness (as in pavataṃ—exuding). Though not etymologically relevant, the homophonous root √pā, meaning “to drink in” does convey a flavor of this salutary and nourishing mind state. Pāmojja’s root is √mud which means either “to be soft” or “to be happy” (Digital Pāli Dictionary). And it shares this root with several other perhaps-familiar, joy-filled words whose meanings augment our understanding. Such words include: muditā—sympathetic joy; anumodana—thanksgiving; mudu—soft, flexible; abhippamodayaṃ—gladdening; and modaka—a globular sweetmeat. This is how pāmojja feels and tastes to me. And so it is.

VI. Conclusion: Appreciating Where We’re At

Having set out with early high hopes of perhaps riding the waterslide of the wellbeing cascade all the way from its peak down and out into the “great ocean” of “true liberation,” we find ourselves still at the mountain’s top, flapping our arms in a light rainfall (Saṃyutta Nikāya 12.23; Dīgha Nikāya 34). But, we have covered some ground. Realizing that the mountain we are standing upon is our own “great mass of suffering apparent here and now,” we inclined toward accepting some of that thick-and-dirtiness (Majjhima Nikāya 13). Looking down that great mass of mountainside, we observed the sukha-to-samādhi whirlpool, questioning the meaning of “happiness,” and coming to feel that, both pragmatically and textually, it is deeper and more encompassing than formerly thought. Looking up, we pondered the clouds of radical awareness and, through etymology, scriptural exploration, and experience, arrived at the conclusion that it would be better to look within; to turn the mind around and glimpse from the yoni-source. And, in an anti-climactic conclusion, we plopped around pixieishly in a piddly-puddle of pāmojja.

Though the great ocean still seems exceedingly far away, there are moments when it seems we can smell the sea. And such wafting scents involuntarily prompt the hopeful recollection, “Just as the great ocean has one taste, the taste of salt, so too this Dhamma and Discipline has one taste, the taste of liberation” (Udāna 5.5). A smile can form as we stand without an umbrella in the midst of the gentle shower. Though our hearts long for the full immersion to be found further downstream, we can let that longing be with the blink of an inner-turned eye, and mindfully settle into the pleasant, present drizzle. There is faith in the causality of wellbeing, so I “need not set the intention, ‘May I realize the knowledge and vision of liberation!’” Indeed, the heart reminds itself, swimming in such depths will be “only natural (dhammatā) … as good habits flow on from one another, and fill up from one another, in going from the near shore to the far” (Aṅguttara Nikāya 10.2).

- (Footnotes and Bibliography can be found in the original Google Doc here.)