Clear Mountain’s pilgrims, both in person and in heart, set a strong intention for our future, ending 2022 at the feet of the masters and under the seat of the Buddha. Here, they recount their experiences.

Clear Mountain’s Aspiration

Through the merit of our practice of giving – learning humility and loving service – may all our adhiṭṭhānas for Clear Mountain Monastery be deeply fulfilled for all of us and for all future generations.

Through the goodness of our practice of precepts – delighting in my own and others’ safety – may all our aspirations for Clear Mountain Monastery blossom for all of us and for all future generations.

Through the power of our practice of meditation – listening to, discussing, and internalizing the Dhamma – may all our determinations for Clear Mountain Monastery reach fruition for all of us and for all future generations.

We hope to bring this pilgrimage, and all it represents, to those who could not come. Below are pilgrims’ accounts of their most meaningful experiences. You may also check out the YouTube roundtable discussion and Community Stories session in which pilgrims reflect on their experiences.

Teachings recorded in Thailand include:

- Q&A with Ajahn Jayasaro about the Buddhist school he helped found: On Buddhist Education: Q&A at Panyaprateep Boarding School | Ajahn Jayasaro

- A guided meditation by Ajahn Jayasaro to the pilgrims: The Relationship Between Mind & Object | Guided Meditation by Ajahn Jayasaro

- Q&A with Ajahn Jayasaro and the pilgrims: Modern American Queries | Q&A by Ajahn Jayasaro

- Q&A with Ajahn Anan and the pilgrims: Ajahn Anan Q&A (Part 1): Emptiness Beyond Doubt & the Body and

Ajahn Anan Q&A (Part 2): Devas & Mara - Talks given by Ajahn Kovilo and Ajahn Nisabho at Wat Marp Jan: Doubt Intelligently (Ajahn Kovilo) and Pilgrimage & the Language of Faith (Ajahn Nisabho)

Finally, several anonymous donors have helped sponsor the purchase and shipping of Clear Mountain Malas. During the pilgrimage, we had beads of locally-sourced Montana agate blessed by many of the teachers we visited and by the pilgrims’ aspiration under the Bodhi Tree. These were strung into malas which you may request at the bottom of the Recitations of Refuge page. They are given freely, as an aid to meditation, a tie to the journey, and a symbol of belonging. May all beings be well!

Ajahn Nisabho

In December, thirty members of Clear Mountain’s community traveled to Thailand and Bodh Gaya on pilgrimage hoping to set the project’s aspiration at the feet of the masters and roots of the Bodhi Tree. To bring a founding group to the tradition’s source seemed essential in establishing the future monastery on the firm ground of lineage.

In the months leading up to the trip we sometimes wondered if the pilgrimage would be worth the months of preparation.

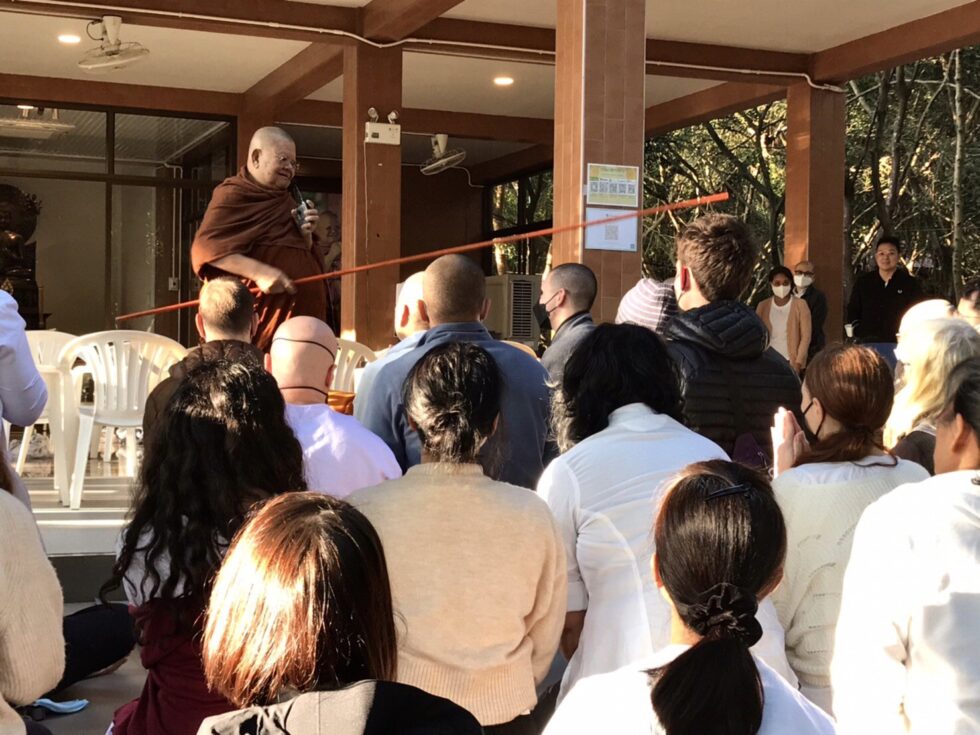

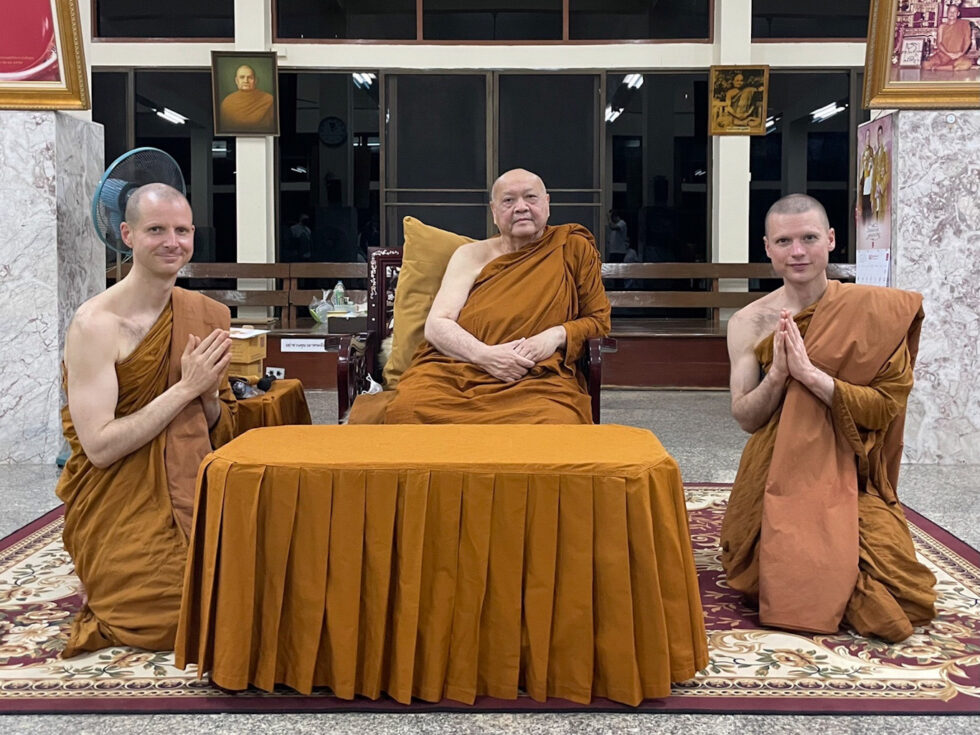

The trip began in Thailand with a flurry of visits to renowned Thai monastics, including Ajahn Anan, Ajahn Suchart, Ajahn Dtun, Ajahn Ganha, and Ajahn Piak. The group also spent nearly two days with Ajahn Jayasaro, visited a Buddhist school he helped found, and spent a night at a center for female monastics in Bangkok. The trip ended with pilgrims meditating together for five days in Bodh Gaya, reciting together each evening the aspiration for Clear Mountain Monastery and all it might become.

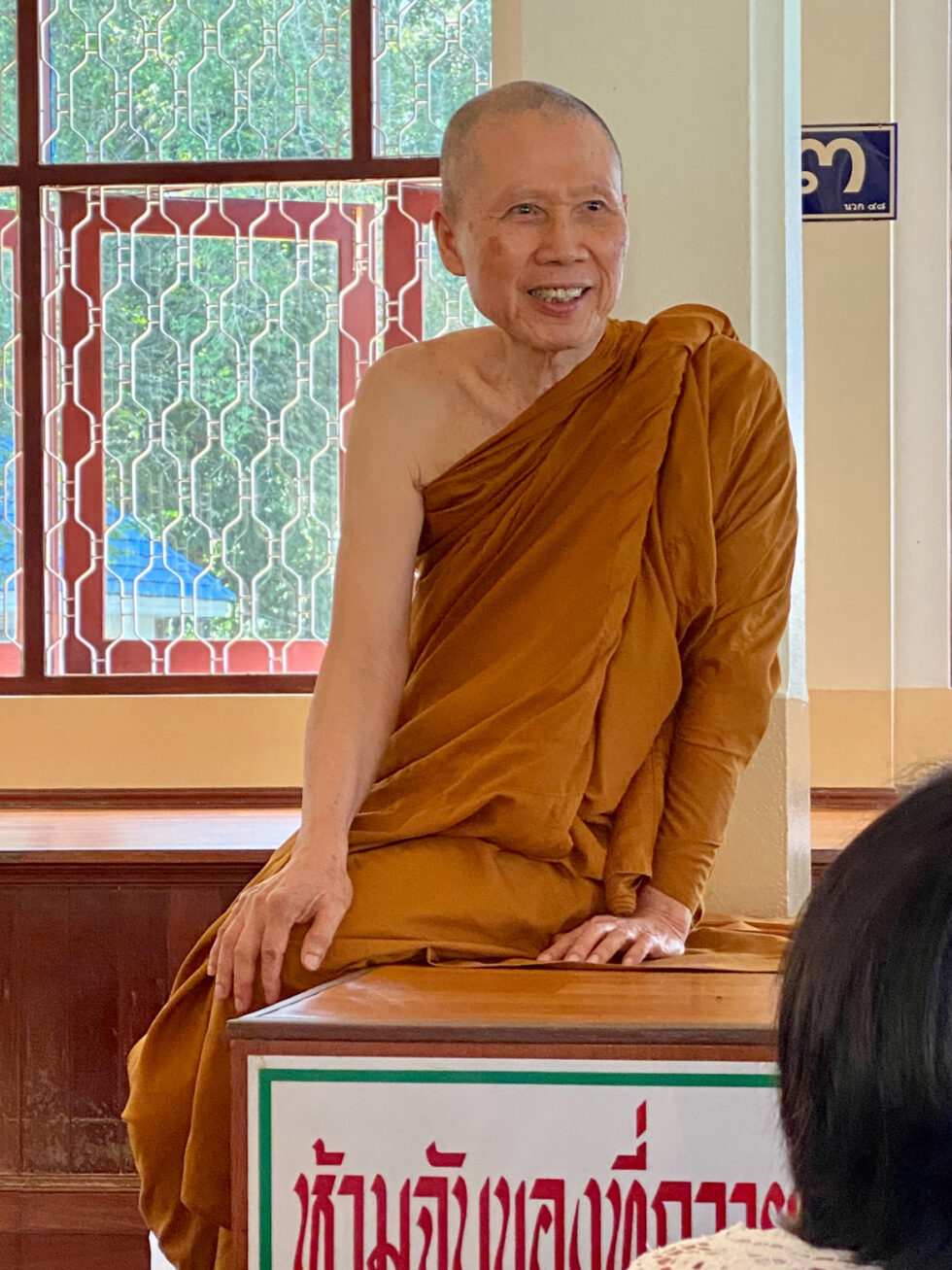

Apart from seeing what monasteries look like in a Buddhist society, pilgrims were changed by encountering teachers of a caliber rare in the world. Some remembered most hearing Luang Por Suchart, a senior teacher renowned for the directness of his teachings, speak about letting go of attachment to the body. One student looked up and in a moment of insight saw him transfigured into a corpse; a teaching on the transitory nature of this form.

Others found themselves called to consider how sincerely they were living the values of their practice by the words of Maechee Paññāsirī, a young nun who spoke for over ninety minutes on what it truly meant to give one’s life to the Dhamma, declaring with fire, “There’s nothing that could cause me to disrobe. I will die first. The path is all that truly matters.” All found themselves moved by the care with which so many teachers received us, answering questions for hours, ensuring our group was cared for, and granting us teachings whose directness was softened by their gaze.

In Bodh Gaya, the pilgrims had the chance to let the teachings of the past seven days sink in, and to think of their and Clear Mountain’s future. It is said that an aspiration made under the Bodhi Tree carries a unique power, and there is something undeniably moving about being part of the sea of faith that swirls around that center—watching hundreds of Tibetans performing full-length prostrations for ten hours daily, Thai monks chanting the twelve links of Dependent Origination in Pali as the Indian sun rises, and Americans meditating quietly under the shade of Bodhi leaves. One member of the group circled the temple complex 108 times—roughly twenty miles of walking—while another spent hours sitting next to Ajahn Achalo, who has meditated over 4,000 hours under the Bodhi Tree. All in the group gathered each evening in front of a pond framed by Tibetan prayer flags to chant and set their intention together for Clear Mountain and all it might become.

On one such evening, the group circled around a lotus-shaped candle we were given in Thailand. After reciting Clear Mountain’s aspiration, several of the group carried the candle down worn stone steps, setting it under the Bodhi Tree as a symbol of our offering the monastery to the Buddha, to future generations, and to Awakening.

Do not worry if you were not able to come in-person. The stories, pictures, and recordings below, and all they carry, will allow the trip to ripple out. All of our hands placed that candle as all of our hearts will carry this vision forward. May it light the paths of all now and all those yet to come.

Ajahn Kovilo

In the words of one of the Pali Canon’s most beloved suttas, our three-week Clear Mountain Monastery pilgrimage to Thailand and India was one of my life’s “highest blessings.” In that sutta – the Maṅgala Sutta (Sn 2.4) – the Buddha elaborates the whole of the Buddhist path in the form of twelve pithy stanzas, each relating a selection of related virtues and capped with the refrain: “These are the highest blessings.” Similar to this discourse, our twelve boon-filled days meeting teachers across Thailand, and settling under the Bodhi Tree, presented and mirrored an array of spiritual qualities ripe with blessings. The Maṅgala verse that best epitomizes our journey for me, and that nicely outlines my four most poignant pilgrimage experiences, rings forth as follows:

“1) Patience, 2) being easy to speak to, 3) seeing samaṇas, and 4) timely Dhamma discussion – these are the highest blessings.”

Patient-endurance or khanti was, in my eyes, impressively embodied by Maechee Paññāsirī – “Splendour of Wisdom.” Besides seeming to announce this grace through her deportment, Maechee Paññāsirī spoke directly to this virtue as being “the quality we need from day one to the end of our journey … [that with which] you can tackle everything.” Hearing her responses to our pilgrims’ questions about gender power imbalances in the Thai Saṅgha, was a profound lesson in nimbleness of perception, personal responsibility-taking, and challenge-facing. Not denying inequalities, she fiercely affirmed, “I see this as a great opportunity … [we can] turn any hardship into compost.” Her natural and serene composure, undoubtedly born from lifetimes of patient insight, is a memory I hope to long keep with me.

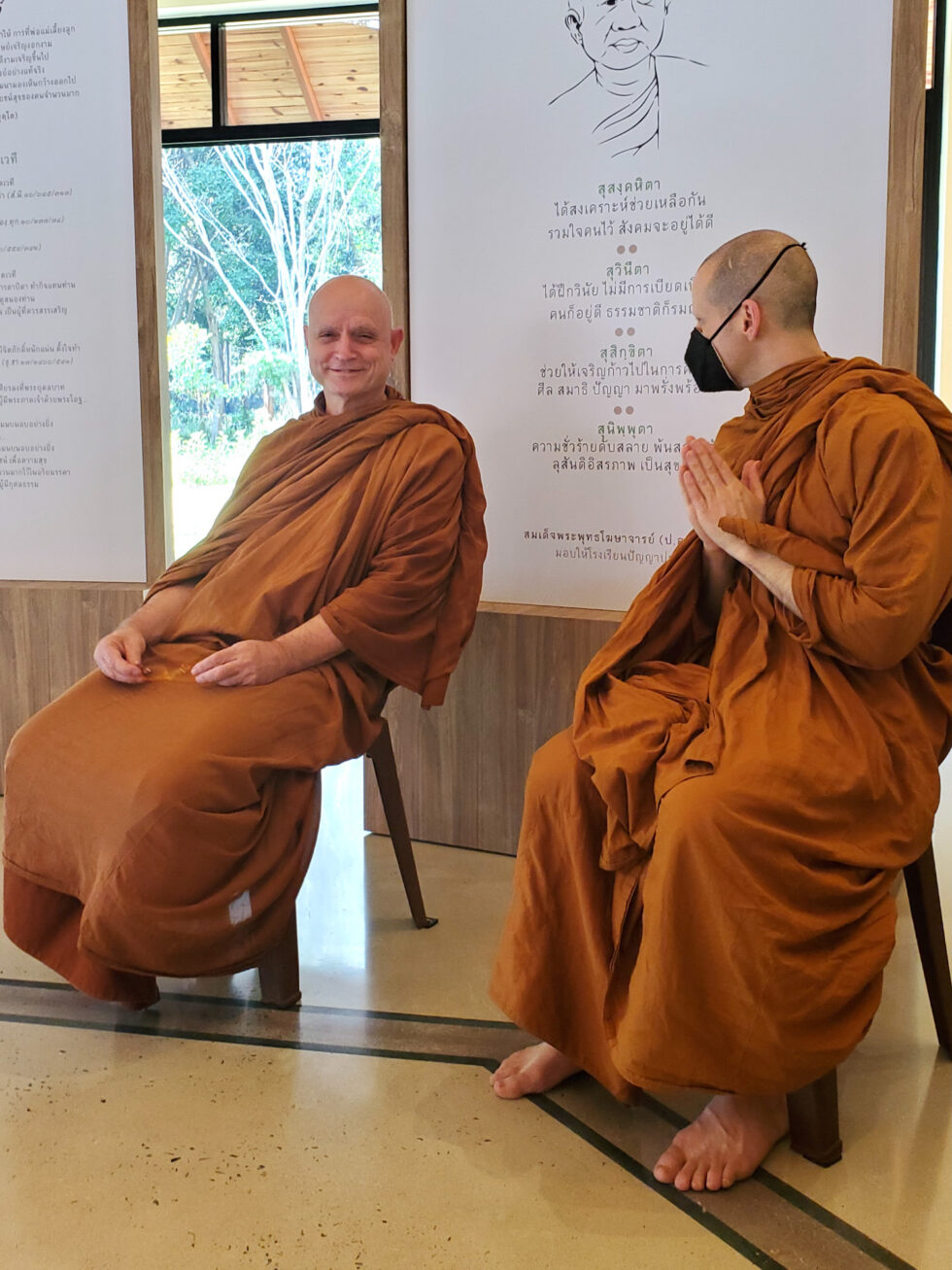

Our next highest blessing, “being easy to speak to,” or sovacassatā, is one I associate with Luang Por Ganhā. Sitting next to him, it felt like his ebullience had no bottom! His extremely easy and broad smile cracked my self-important defenses, and his eccentric, long-stick mettā-taps tenderized my heart. In addition to the multiple hours he gave to our group, he further opened the door of his personal dwelling – to an extent that I’ve never witnessed in another human – for Ajahn Nisabho and me to come and seek personal advice. Though he was, at the time, actively receiving medical treatment in a very vulnerable and compromised posture, he received us into his space in a way and to a degree that wordlessly proclaimed, “I have no personal space. You are welcome.” This was a profound, living example of one of his most reiterated teachings, that of sie-sala or “fearless giving-up of self.”

The third teaching in this verse and my third pilgrimage takeaway is “seeing samaṇas” or true spiritual athletes. While literally and mundanely referring to any religious seeker, the Buddha often spoke of the genuine samaṇa as being one who has actually attained to some level of Enlightenment, from Stream Entry on up, and it is my faith that several of the teachers we visited, bowed to, listened to, and learned from were, indeed, such authentic and noble Saṇgha members. Further I believe, in line with this Maṅgala Sutta and with the Kīṭāgiri Sutta (MN 70), that for those who are open to it, merely seeing such teachers can be a boon and one of life’s highest blessings. And this is great because, although not all of the talks were recorded and although my memory of their words is fleeting, I can still vividly recollect their various faces – piercing, laughing, consoling, radiant, utterly compassionate, magnanimous, and courageous. May the memory of these fantastic and bright faces never dim from my mind’s eye!

The final highest blessing in this verse extols “timely Dhamma discussion,” which beautifully summarizes the pilgrimage experience as a whole, as well as the individual, one-on-two, personal interactions that Ajahn Nisabho and I had the extreme good fortune to have with each and every teacher we visited. Perhaps unbeknownst to most of the other pilgrims, Ajahn Nisabho and I shamelessly, repeatedly, and regularly played our VIB (Very Important Bhikkhu) monk cards, in order to receive supplementary audiences with all these luminaries. Truth be told, though we are not actually “very important bhikkhus,” we were persistently so bold as to stick around after group interviews to request special meetings with these teachers. Owing to those teachers’ gentle care and loving largess, we were never refused, but time-and-time again invited to sit at these masters’ feet to receive their defilement-decimating metta rays. May I never forget the Dhammic connections sown with our teachers at their respective huts, dining halls, reception sālas, antechambers, bamboo platforms, and along their paths!

May the time that we have all taken to recollect and write these pilgrimage reflections be – in line with the Kīṭāgiri Sutta referenced above – an express means for embedding, memorizing, examining, and reflectively accepting the Dhamma we’ve heard. May this give rise to zeal, application, striving, and realization of the highest truth, the supreme blessing of Nibbāna!

Katie McKenna

Despite growing up in a conservative-leaning college town in the Midwest, as a child I often wondered about the existence of other universes, celestial beings, and humans with powers beyond what could be explained by science. Hearing about my mom’s faith in rebirth and kamma, and listening to my grandma’s stories of witnessing ghosts and angels, made me desire to have my own experiences that were beyond the materialistic world.

Moving into my 30’s and no longer finding meaning in the career I had built or in the long-term relationship that was loving but predicated on fulfilling sense pleasures only made my longing more urgent. Feeling unfulfilled, I eventually left my relationship, quit my job, and spent the fall and winter serving at monasteries and sitting silent retreats in California.

I savored quiet mornings reading the Majjhima Nikāya and relished stories from monks and nuns who, after sitting at the feet of the masters, were so filled with faith that they decided to ordain. But from time to time, tiny threads of doubt would still arise in my mind.

What if I was deluded and rebirth wasn’t real? Was Nibbāna actually possible? If I kept following this path of renunciation, would I be disappointed?

I always brushed the doubts aside (luckily, they were fairly small) and kept doing my practices, but there was still a yearning to come and see for myself, ehipassiko, and go to the source.

Going on pilgrimage to Thailand and India fulfilled that desire.

From the first evening on the trip, when we settled into Wat Marp Jan, my doubts dissipated, and my faith deepened in a way that I didn’t know was possible.

There, I sat in meditation in the open-air Sala, listening to dozens of monks and lay people chanting in Pali and Thai. With a Buddha rupa encircled by the image of 7 nagas in front of us, I experienced a full-body knowing.

Filled with gratitude and devotion, I thought to myself, “There is something more going on than I can see with my eyes. Don’t be heedless. Don’t waste this precious human birth.”

Later, at the same monastery, while sitting in the Bodhisattva Vihara, I suddenly felt a complete and profound sense of safety. When I turned around to see if perhaps another monk had entered the room, it was just myself and two other laity.

These types of experiences only continued to occur along our journey.

Ajahn Suchart’s ability to look at me with kind, but piercing eyes and teach me the importance of body contemplation. A wooden carving of the Mahaparinibbana at Ajahn Jandee’s had such a powerful effect on me that it made me weep. Ajahn Dtun’s impeccable mindfulness reminded me of the profound beauty of simplicity and presence.

Thailand left me awe-inspired, with deep faith in Nibbāna and the Triple Gem, and with a deeper understanding of the Third and Fourth Noble Truths —that there is a cessation of suffering and that the way leading out of suffering is the Noble Eightfold Path. But the trip wouldn’t have been complete without the whole of the Buddha’s teaching. Traveling to Bihar, one of the poorest regions in India, was a reminder of the First and Second Noble Truths—that there is suffering and that there is a cause of suffering.

Making our way by foot from the Root Institute where we were staying to the Maha Bodhi Temple, I was struck by both the beauty and the suffering of so many around us. As we walked, children grabbed onto our arms and tugged on our shirts, begging for food and money. One day, a woman with two babies in tow asked us to buy them a meal. Her eyes looked somber as she showed us the scars on her stomach and hands from an acid burn, but when she started talking about her children, she broke into a smile.

Seeing all of this suffering so visibly in the land where the Buddha lived, awakened, and taught, allowed me to imagine how he must have felt when he witnessed the first three heavenly messengers of sickness, aging, and death, after he left the palace grounds.

Yet that potential indicated by the fourth heavenly messenger, a renunciant, was also present. Taking multiple trips to the Mahabodhi Temple grounds, I witnessed hundreds of monks and nuns from various lineages, meditating, chanting, prostrating, and burning incense—many in the name of deep faith and devotion. The sight of so many monastics coming to such a holy place was a reminder that life is sacred and to spend our days wisely.

As Bhikkhu Bodhi puts it in his essay, Meeting the Divine Messengers,

“Beneath the symbolic veneer of the ancient legend we can see that Prince Siddhattha’s youthful sojourn in the palace was not so different from the way in which most of us today pass our entire lives — often, sadly, until it is too late to strike out in a new direction. Our homes may not be royal palaces, and the wealth at our disposal may not approach anywhere near that of a North Indian rajah, but we share with the young Prince Siddhattha a blissful (and often willful) oblivion to stark realities that are constantly thrusting themselves on our attention. If the Dhamma is to be more than the bland, humdrum background of a comfortable life, if it is to become the inspiring, sometimes grating voice that steers us on to the great path of awakening, we ourselves must emulate the Bodhisatta in his process of maturation. We must join him on that journey outside the palace walls — the walls of our own self-assuring preconceptions — and see for ourselves the divine messengers we so often miss because our eyes are fixed on ‘more important things,’ i.e., on our mundane preoccupations and goals.”

It was through this journey of meeting awakened beings, witnessing the devotion of the Sangha, and seeing with more clarity the truth of suffering, that my faith deepened and any lingering doubts disappeared.

Without experiencing the whole of this pilgrimage, I don’t know if I would be ready to fully open to what’s next on my path. I look forward to bringing this devotion more deeply into my practice over the coming months.

Daniel Sullivan

After several months of travel, I arrive early to Wat Marp Jan. Bronchitis has come along for the ride; right away, I am shown the full extent of care and kindness from monastery members and early-arriving pilgrims alike. The label on a tea bag I’m given reads, “Give thanks for unknown blessings that are already on their way.” I am offered electrolytes, cough drops, and more snacks than I can consume. Grateful and bright, I begin a list in my journal of their kind deeds. Despite exhaustion and my near constant presence on a cot in the scenic hillside dormitory where we stay, friendship provides a bright beginning.

It is a greater challenge when we visit new places. I await a heightened spiritual experience in Thailand, and while Ajahn Dtun definitely surprises me with a felt presence I cannot explain, I otherwise have the same drab emotions as always: no sudden insights, no stunned awakening, no awestruck clarity. My expectations are tempered by the words of renowned teachers, which percolate as I repeatedly sit with a sluggish mind, wake myself coughing, or pile into a van wearing a mask and a grumpy countenance. When I ask varied questions of the same thread, they point again and again to mindfulness. This repeated message I hear reminds me that Nibbāna can be found in the mundane: nothing extra, nothing additional. This is not a practice dependent on spiritual highs. Peace is presence, setting down, unbinding. By the time Ajahn Jayasaro is giving a guided meditation to us across a pool of blooming lotus, I have stopped looking for something to happen, and bright clarity knocks at the door once again. I carry it onto the plane to India.

This is a land of sensory overwhelm, which I anticipate. I guard my sense doors; every direction, there is a pull to see, to hear, to excite, to fear. Watching the ground with peripheral vision open, I ignore the calls of shopkeepers and the desire to eyeball their brightly colored wares. Rickshaw drivers shout greetings or follow me insistently, and a polio-stricken beggar walks on his hands through the dirt to grab at my pant leg. It is difficult to avoid their persistence without feeling heartless, yet I simultaneously feel I am perceived less like a person and more like a giant, walking wallet.

Regardless, carefully held attention serves me well. At the Mahabodhi Temple, there is a new sensory experience waiting. Thanks to my method of navigating, I am held in a broad, expansive awareness during my first sit under the tree. My mind is calm despite throngs of voices and the sting of smog in my still-raw throat. I am surrounded by sound, but not overwhelmed. The first two days, I settle into a space that feels like a drop of water in the ocean, diffusing outward. My presence integrates quietly; I am nothing in a sea of everything. After Thailand, I am open to this more gentle experience, but in the coming days on the Temple grounds, I am moved beyond words.

“I have heard that on one occasion the Blessed One was dwelling among the Sakyans at Kapilavatthu in the Great Wood, together with a large Sangha of approximately five hundred bhikkhus, all of them arahants. And most of the devatas from ten world-systems had gathered in order to see the Blessed One and the Bhikkhu Sangha…

White devas, ruddy-green devas, dawn-devas have come with the Veghanas headed by devas totally in white. The Vicakkhanas have come. Sadamatta, Haragajas, and the prestigious multi-coloreds, Pajunna, the thunderer, who brings rain in all directions: These ten ten-fold hosts, all of varied hue, powerful, effulgent, glamorous, prestigious, rejoicing, have approached the monks’ forest meeting.

The Khemiyas, Tusitas, and Yamas, the prestigious Katthakas, Lambitakas, and Lama chiefs, the Jotinamas and Asavas, the Nimmanaratis have come, as have the Paranimmitas. These ten ten-fold hosts, all of varied hue, powerful, effulgent, glamorous, prestigious, rejoicing, have approached the monks’ forest meeting.

These sixty deva groups, all of varied hue, have come arranged in order, together with others in like manner [thinking:] ‘We’ll see the one who has transcended birth, who has no bounds, who has crossed over the flood, fermentation-free, the Mighty One, crossing over the flood like the moon emerging from the dark fortnight.’”

(Excerpts, DN 20, trans. Thanissaro Bhikkhu)

Now, I am myself surrounded by those who attend the seat of the Buddha: where he discovered and took to fulfillment wisdom of the Four Noble Truths. We are circumambulating, meditating, chanting in a hundred languages and a thousand voices, each and every devoted deeply to the same wish: that we should also be free from the bonds of human suffering. I tread barefoot past seated rows of meditators, or sit; monks swish by in robes of garnet, ochre, and umber. I am in white, struggling to hold the dark, smooth beads of my mala as I count 108 full-length prostrations. Garlands of yellow and orange marigolds hang abundantly, adorning stone carved Buddhas. Even in the early morning, the sun rising through a silver haze, devotion resounds across the well-swept marble floors. I am transformed here. I am one of the thousands of devas with the name of the Buddha in my throat. I am nobody at all. I am devotion to the teacher of the most significant words I’ve ever heard.

During a mealtime away from the tree, I met a nun from a monastery I visited before pilgrimage. Grinning, she tells me to make a wish under the tree. Ajahn Nisabho, too, suggests we make adhiṭṭhānas (resolutions) here. I write a short list in my journal, private. After one evening meeting with the rest of the members of the group, I sit in meditation, waiting to lay my hands on the stone in front of the tree unrushed. So many of us have jumped into a Clear Mountain stream, leading us breathless and joyful into cool, clear water, drinking deeply of a wholesome practice and a bright path previously unimagined. I, for one, am stunned by this new, pure love into which I’ve stumbled. It is embodied not just by our very own Ajahns, but by the other pilgrims, present both in person and in heart, in whose conduct I consistently see prosperity and hope.

May Clear Mountain Monastery be a place where people like me, all of us, and all future generations can practice the path of Dhamma to our full aspiration and to our full potential.

Miles Rossow

For the Clear Mountain pilgrimage, my primary intention was to investigate options for potential ordination. For years, I’ve vacillated between choosing life as a monastic running headlong towards Nibbāna and life with a sweet honey to grow with in the Dhamma. Now 32-years-old, there’s increasing pressure to figure out what the heck I’m doing with this life. Although I’ve seen monasticism as the higher path, it’s been difficult to put aside the notion of getting chummy with a bodacious Buddha babe. Before the trip, I felt strongly that the latter would be more spiritually fruitful for me.

Before arriving at Wat Marp Jan, I already felt a deep affinity for Luang Por Anan, as his mettā & wisdom are very compelling in his online Dhamma talks. Luang Por generously blessed the pilgrims with two Q&A sessions in which I asked him about my indecision around ordination. With his characteristic gentleness, he encouraged me not to worry so much about ordaining, to take my time, and to focus on building my pāramīs. This was refreshing to hear and eased the pressure I’d been putting on myself to choose a path ASAP. A couple more questions were asked and the Q&A came to a close, but before it totally ended, Luang Por looked at me and asked my name, causing a bit of excitement and panic. Eek! Why does he want to know my name? “Miles,” I told him, and he tried saying it a couple times. Then he told me, “Miles, set your heart on ordaining,” and all the other pilgrims laughed and gave a teasing “oooohh!” I was a bit embarrassed because it was in front of everyone, but more prominently & surprisingly, a great joy arose upon hearing this. It felt like he might have confidence that I could be a good monk, and from someone like him, that’s powerful. He also might’ve mettā-blasted me when he said that, which would be a neat trick to get someone to believe what you’re saying. Either way, it worked, as I flopped back onto the side of favoring ordination. The joy of that moment persisted for a couple days and even still, when recollecting his words, I feel warmth and confidence.

The pilgrims soon marched onward, and a few days later, we had a Q&A with Tahn Ajahn Jayasaro’s disciple Maechee Paññāsirī, who just spent 4 years in solitude. Although this was her first time speaking in front of a group as a maechi, that didn’t stop her from giving one of the most inspiring talks of the entire pilgrimage. Her wisdom came through in an emphatic, no-punches-pulled style of speaking that resonated deeply with me.

I asked her how to deal with loved ones who do not support the monastic aspiration and who require a lot of attention to keep happy, which precludes extensive solitude. Maechee Paññāsirī’s response was multi-faceted, but it partly focused on being a living example of the transformative powers of the practice. As you develop spiritually, you will become dear company to those around you, and though you may depart for long periods, you will leave them with love rather than just turning away and saying, “Don’t bother me, I have a profound goal to achieve. Goodbye!” To be honest, her answer inspired some shame in me because there has been a desire to get away from some people instead of honoring their fears around my monastic considerations and being a good example of the practice.

The most impactful parts of her talk actually came as she answered other people’s questions but seemed to speak directly to me. She seemed to intuit that I was lazy in my practice, and although she was answering other peoples’ questions, she often looked me in the eyes for long stretches and said things like, “Set up rules for yourself and stick to them. If you cannot do this, the monastic form will be impossible for you. Self discipline must remain the same both publicly and privately.” Oof. Right to the core. Here’s another one: “If you don’t even have full commitment and sincerity for seeking truth, even if good kamma comes to you and you put robes on, you’re gonna have difficulties. If your commitment isn’t full, you won’t go very far.” And another: “In Seattle, you can build your mobile monastery around yourself. That way your parents can never stop you.” Cue everyone’s laughter because they know she’s talking about me. She also mentioned multiple times the benefits of keeping eight precepts.

I felt justifiably chastised and simultaneously fired up for my practice.

Some time later, we found ourselves under the Mahabodhi Tree in Bodh Gaya, traversing and sitting where the Buddha attained Full Awakening. During our stay, Ajahn Achalo—a seasoned disciple of Luang Por Anan—offered us many wise reflections. In particular, he discussed the great strength of setting intentions under the Mahabodhi Tree and encouraged us to do so.

Following Luang Por Anan’s encouragement to set my heart on ordaining, Maechee Paññāsirī’s exhortation to strive with diligence & sincerity, and Ajahn Achalo’s advice to set an intention under the Mahabodhi Tree, I felt compelled to take on the adhiṭṭāna to observe the eight precepts until 2024, and so I did. Perhaps it is the case that my adhiṭṭāna was strengthened by the mere perception that the Mahabodhi Tree is a potent place for setting intentions, and I was certainly primed by the Ajahns to set such an intention; however, I like to remain open to the possibility of energies and formless beings at the Mahabodhi Tree that I am not yet privy to that help us fulfill noble intentions. Either way, this adhiṭṭāna felt particularly powerful. Although keeping eight precepts until 2024 will be challenging, I am confident that it was the right decision for my practice and that it will offer nourishing soil for me to grow & harvest the fruits of Dhamma.

Willerie Razote

I had not wanted to go to India. I initially planned to begin and end my Clear Mountain Pilgrimage in Thailand. Not because I thought India would be daunting or to go to Bodhgaya meant I would be going to Bihar, one of the poorest states in India. And that in being in one of the poorest states, I would see poverty and suffering beyond what I’m used to, and my heart would have no choice but to hold the weight of immense suffering that my eyes can only take in but be helpless in carrying. I had not wanted to go to India because my work just took me there earlier in the year, and – in being truthful, which gives me a sense of shame to admit – I have not felt compelled to go to Bodhgaya.

It took convincing from a friend to add the second part of the pilgrimage onto my itinerary. He had spent a week meditating under the Bodhi Tree a few years back and was convinced I also had to experience it. Plus, he jokingly threatened me with the idea that if I should die within the year, I would have at least covered three out of the four holy Buddhist sites, perhaps guaranteeing it more so than if it were only two that I would come across the Dhamma in my future rebirths. And so, a flight from Bangkok to Bodhgaya was added on. Along with this new leg came a new intention that I would keep close: To get to know the Buddha.

Despite a not so perfect welcome at the airport once we landed, it was in Bodhgaya that my mind was most still. Perhaps the serenity was spurred on by just having sat at the feet of generous and wise master teachers that one only dreams of doing. Perhaps it was because the knowledge of just how special Clear Mountain sangha was solidified in the days prior. I witnessed over and again just how supportive and loving both our resident monastics Ajahn Kovilo and Ajahn Nisabho are, that I had confidence in them and trust in their guidance. And maybe because I had the same trust in the laity and knew in times of difficulty, they were willing to share it with me. And maybe because I saw how sensitive the pilgrims’ hearts were to the poverty and suffering all around them, which gave me relief because that was how my heart reacted when I first came to India to work in understanding health inequity in poor and marginalized communities. Sensitive hearts bear pure intentions.

In the stillness of my mind, the Bodhi Tree appeared in my visual field. Strong, eternal, unwavering. My mind mirrored it. Secure, expansive, unmoving. In this stillness, I was able to take in the quiet beauty of the sounds, the energies, the flow. I witnessed them circumambulating the bodhi tree of my own mind. Circumambulating faster and faster around a stillness that remained undisturbed. How beautiful it was to start understanding the pull of Bodhgaya in this way.

Keeping my intention in sight, I did get to know the Buddha, not directly but by witnessing how far and wide his teachings reverberated. His reach can be seen in the different colored robes, and the faces and skin color of the bodies that wore them. It can be heard in the different languages and the different pace in which the chants were chanted. It was in the different ways of prostrating, from full prostrations to small bows. The Universal Sangha is like a well-made colorful cloth, woven with threads of different sizes, textures, and dyed in various colors. Though different in all ways, what they shared was the palpable love for the Buddha.

If the love for the Buddha is like the spool that each thread winds around, then I find myself wanting to wrap around it. I recently felt compelled to go back to Bodhgaya. Not because I want to or need to, but because I’m supposed to. Maybe I’m supposed to build on my intention to get to know the Buddha, and my three days there was just the starting point – the intro. And so, I find myself booking my eighth flight back to India, a country I’ve felt was my second home and its people my extended relatives. This next trip I plan on adding 108 hours under the Bodhi Tree to continue and build on my original intention – this time the extended intro.

Amy Boggs

I know people don’t often launch from zero international travel experience into a multi-week pilgrimage, but that’s exactly what I did. When presented with an opportunity to pay homage to renowned Thai Forest Monks, meditate in their monasteries and then visit the site of the Buddha’s awakening, the Bodhi Tree, the answer was simple: Yes, I’ll go!

The first leg of the trip was the three hour drive from Portland to Seattle.

I traveled with my close friend and housemate, Mike. In the airport I glanced down and noticed just how much lighter his bags were than mine: many months before he’d begun the process of preparing to go forth as a Buddhist monk, beginning a life of renunciation, owning very few things.

We would find out soon that many young men on the pilgrimage had the same idea in mind!

Our first destination in Thailand was Wat Marp Jan, the monastery of Ajahn Anan. This monastery is tucked into the lush jungle, built into the hillside, so that your climb to the meditation hall is rewarded with views overlooking the dense and verdant valley below. In the early mornings, I would do walking meditation in the outdoor foyer so that I could soak in the sounds of the birds and insects awakening for the day, singing, cluttering and calling forth the symphony of the jungle that spilled out over the tops of the trees as the sunrise turned the leaves gold and pink.

We were treated to three dhamma talks with Ajahn Anan during our stay here. He invited questions from our group and radiated kindness in his answers.

My heart filled with joy when he broke into a smile.

After a few days, we settled into a routine here. After morning puja, we’d head down the hill to have a snack (usually bananas picked from the trees on site and juice). We’d kneel and take our place in line, so when the monks returned from alms round, we could spoon rice or small treats in their bowls. I have offered food to monastics before, but there was something strikingly humble and ancient about this simple act and how warmly it was received by the monastics. I looked forward to it each day.

Our stay overlapped with Ajahn Anan’s online retreat and in the evenings after puja, we received additional dhamma talks.

Before leaving Portland, I had tried to prepare myself for the discomfort of a trip like this: the long flight and hours spent on the floor in meditation. I was definitely not prepared for how much physical pain I was going to be in once the trip was underway. In one of our evening check-ins with Ajahn Nisabho and Ajahn Kovilo, when it was my turn to speak, all I could eek out was strained, “I’m struggling.”

That next morning, I gave myself a little break and slept in so I would have time to walk over to the secret garden Ajahn Nisabho had shown us the evening before. Down a winding path with banana leaves lazily draped in a canopy above, I drank my coffee as the sun rose and I began to regain my center. I gave myself a little pep talk: 5am puja, no problem! Hard floors, I got this.

Little was I to know, a mere twenty minutes later, I was about to get wildly thrown off course.

This was our last morning at Wat Marp Jan and everyone had packed in the dark and prepared to set off on an ambitious schedule of visiting 2-3 monasteries a day, knowing that this was a once in a lifetime chance to meet these Thai meditation masters – so we were ready for a breakneck pace.

As I was walking back to the women’s house with my coffee in hand, a lightness in my heart, Mike pulled me aside to tell me some bad news: he tested positive for Covid that morning. His symptoms were very mild, but we wouldn’t be able to stay with the group. Earlier in the trip, the Ajahns had asked us to pair up to ensure no one got lost on the trip – Mike was my “buddy-sattva” so we were in this together.

My heart began to fall, but then he said: “I’ve made arrangements for us to quarantine at a nearby resort.” I stopped for a second: “Did you say resort?”

A ten minute tuk-tuk ride later, and we were at Tamnampar, getting separate rooms and asking ourselves what was going to become of this trip. After settling in, we decided to tour the sprawling resort. I don’t think either of us could have anticipated this turn of events but as we walked around, the beauty that surrounded us began to sink in.

And then we turned the corner and saw the water park.

It was obvious that we were going to stay on the 8 precepts and continue with Ajahn Anan’s online retreat schedule – we didn’t want this to feel like too much of a vacation and lose the container of the pilgrimage. That being said, I did buy a bathing suit.

Mike and I would meet for morning puja on the outdoor deck to one of our rooms, and eat our one meal of the day at the hotel restaurant. After more meditation, we’d break in the afternoon. Mike would go back to his room to rest. I would go down the water slide.

I loved the pace of our days there: we’d walk to one of the outdoor verandas and meditate along the paths lined with bromeliads and orchids, with giant iridescent butterflies swooping by. I began to have the most relaxing, insightful and moving meditation experiences of my life. Mike would play the dhamma talks the pilgrims had recorded and posted online from the various monasteries they were visiting. The teachings began to deeply reach my heart, and Mike told me later that he’d look over at me during a talk and I would have tears streaming down my face.

Michael Joliffe

As my friend and I walk home on the streets of Bodh Gaya after the Mahabodhi temple closes for the evening, an explosion of light and sound erupts madly from behind a building, splitting the quiet darkness and bearing down on us like a mobile miniature circus. We’re swallowed by blaring Indian music punctuated with the staccato suction cup sound of tabla, a galaxy of bright neon lights creating a spectral aura around the tuk tuk in the smoggy air, casting the driver’s hungry face with a ghastly pale. A halting negotiation in broken English ensues, and my friend and I find ourselves in the back of the vehicle bouncing wildly over heavily rutted roads. At one point, while I desperately grip the seat back and brace against the ceiling to ward off the giant bumps, I look over at my friend with grim determination. He beams at me, his hands in his lap, and says, “it might be easier to just let it bounce you around.” I immediately see how much I’ve been trying to control the situation; all the situations. I relax, and from that moment forward adopt his advice as a mantra for everything India throws at me. I just let it bounce me around. And somewhere amidst the chaos of megaphone chanting, incessant horn honking, pushy peddlers, crippled beggars, ravenous mosquitoes, a bout of food poisoning, and smells I can’t and don’t want to identify, I see a glimmer of the peace wise beings counsel does not depend on external circumstances. My heart can be that still, dark night the brash and unpredictable tuk tuk of life moves through without leaving any residue.

Dave Tatro

Wat Marp Jan is a refuge within the Three Refuges. Waking up there on our first full day in Thailand, the sun was shining and filtered through the heavy jungle vegetation along the curving roads leading to various buildings. Birds called so strangely to each other from above. As we walked and got oriented to the layout of this spiritual campus, a tangible and jubilant feeling of expectation seemed to gently vibrate from the surroundings. Although we were so pleased to be there, it also seemed like a type of nature-happiness maintained itself here. Even the Koi fish in the waters below the bridge seemed playful and welcoming, twisting and turning in the water.

The central meditation hall created immediate reverence without saying one word. To sit in daytime meditation there was a spatial experience, with its high ceiling, deep length, and captivating Buddha statue at the head of this cavernous room. Inside this commanding, comforting place was a fortifying place to still the mind – and right outside, the brightness and lush reminder of the wild world, with all its new animal sounds – it set a tone for tranquility in such a traditional setting – the type of place that to set foot in, lent physical, visual, tactile relevance to something only imagined previously. There was a timeless quality about the place, and a knowledge that Ajahn Anan’s decades-long momentum there, as a renowned renunciant teacher, complemented the respect that rose to the top of mind with every step taken there.

And on the other side of a different day, a nighttime meditation and dhamma talk from Ajahn Jayasaro, on the grounds where he resides. As dusk turned to dark, we sat near the water’s edge of a large pond. It was a refreshing night, the silence settled down with us, as frog voices and a house party somewhere in the distance created an unlikely reminder of harmony, mudita, and gratitude. Sitting in easeful concentration with a group of fellow seekers, students of the Buddha in the 21st century. There was a camaraderie in the quiet. We were there for many of the same reasons with a “goodwillingness” to share something too rare to take for granted.

Ajahn Jayasaro’s familiar voice rounded out the end of this nocturnal meditation in nature. He shared a dhamma talk with us which was as soothing as it was offering something important. Sitting in the dark of a Thailand night, hearing the words of someone so dedicated to describing the trajectory of liberation in this life – made me, and makes me, so grateful to have had this chance to recondition and re-set my priorities while alive in this world.

And it was this way spending time with and hearing from all the great teachers who made space for us at their monasteries and who gave genuine care to us, who had come to learn and understand more about the roots of this holy way of living and dying and moving and changing. Teachings that aren’t easy to articulate here, were soaked up in quiet ways, in overall experience and observation of the Buddha’s legacy, alive and as pertinent as ever in Thailand, just to name one culture. To call the experience of witnessing this, being invited to take part – to call it humbling, does work in a conventional sense. But there was something stronger than that – it was validating and propelling in ways that will last for a long time.

Charles Jasper

There were many moments worth honoring. As a group, we traveled well together. Not without bumps and not without challenging circumstances. But as a team we seemingly took Luang Por Passano’s guidance to heart, to practice peace within one self and among the group.

Secondly, but probably more significantly than any detail I could fathom in words was the profound serenity and sense of ease that emanated from the face, eyes, and whole beings of several of the Ajahns. I was taken first by the smile of Ajahn Suchart, whose presence seemed seamless and inherently warm. Others whose serenity was palpable were Ajahns Dtun, Jandee, and especially Ajahn Jayasaro, whose educational projects are undeniably the richest gifts of Dhamma to the world writ large that I’ve encountered in 70 years of circling this medium sized star.

Boundless gratitude to Ajahn Kovilo and Ajahn Nisabho for spearheading this pilgrimage, and for pointing out that the emergent Naga of the heavenly realm is in fact emerging from the lower forms and associated kilesas. In other words, there is hope.

Sarah Conover

For various reasons, Doug and I, Ajahn Nisabho’s parents, couldn’t come on this pilgrimage to inaugurate the Clear Mountain Monastery project. Subsequently, I had an anticipatory case of FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) which turned into a serious case of BAMO (Bummed About Missing Out) when the December date of the pilgrim’s flight to Thailand at last arrived. Seeing the first blog photo of Luang Por Passano’s remarkably “coincidental” intersecting with Ajahn Nisabho in the Bangkok airport (a bit like the Buddhist metaphor for the rarity of encountering the dhamma in one’s lifetime) let me know that greater forces were at work and that everyone was exactly where they needed to be, including me.

Hopping on the blog first thing in the morning became our daily “news” feed—I’d learn exactly where they’d been and who they’d seen the previous day. While the pilgrims on the other side of the world slept, I smiled recognizing some of the familiar places and teachers from our past trips, smiled at photos of our sangha members walking across the marble-sleek floors perched over the jungle at Wat Marp Jan’s highest mountain sala. Walking meditation on the sala’s balcony remains one of my most glorious memories of Thailand. I smiled at photographs of the group’s Q&A’s with Ajahn Anan—I could feel again the unshakable peace he radiates to one and all.

I hadn’t anticipated how important the daily blog would become to me. The nostalgia for the inimitable cacophony of Thailand’s forests compelled me to eventually ask if a pilgrim could record the ambient sound. Someone read my request and posted a snippet. Through gorgeous photos of stunning monasteries that I’d not visited and the blog reports of discussions with senior teachers I’d not yet met, I sensed that the pilgrims were greatly impacted and it gave me much mudita, shared joy. Photos of one meal wherein local laity had taken hours (or days?) to carve the fruit into flamboyant tropical flowers—a heavenly feast for the eyes and appetites—seemed beyond generous. Not only do the Clear Mountain pilgrims now have an idea of the power of the Thai Forest teachings amplified in its own soil, the beauty a monastery can achieve aesthetically, but they also experienced the graciousness with which local supporters freely offer hospitality to seekers. Nothing expected in return. All these aspects can be models for our future monastery.

I studied the pilgrim’s faces daily in the photos and sensed them opening with more and more ease and perhaps even wonder as the trip continued into India. I suspected most of the travelers would be changed by this trip—some had never left North America—and their heartfelt reports upon returning confirmed that this was so. It will take some time for each of them to metabolize the learnings, but a commitment of the heart to Clear Mountain’s project is now palpable.

Fairly quickly, my BAMO vis a vis the pilgrimage transformed into a sustained opportunity for mudita. The energy to forge ahead with Clear Mountain has a momentum from the pilgrimage that spills over to the rest of us, the community, whether we were there or not. Alejandro’s pilgrimage reflection during the all-night vigil on New Year’s Eve confirmed that no one need feel left out of the brightness and energy born of the journey. We are all pilgrims in the dhamma traveling together in community.

Mary Webster

I did not anticipate the Clear Mountain Monastery’s pilgrimage to the holy sites of Buddhism would have such an effect on me. I had expected to simply view the photos and read the pilgrim’s words much as a mother would view the photos and letters of her children from summer camp: with loving interest but removed from the actual experiences.

In actuality, the pilgrimage was not distant: it was close, visceral and inspiring. First came the pictures of arrival and I looked at the familiar faces realizing “This is really happening.” Then came the photos of the holy sites with each monastery unique in its presentation and expression of the Dhamma. I pored over the photos and imagined sitting in each of these incredible spots. Then came photos of the Venerable Teachers and I was captivated by their presence- so powerful in even a still shot.

My meditations began to flower into deep metta as I experienced the kindness of the pilgrims who were keeping me in the loop. I listened to the renowned teachers and recognized the depth of practice and the development possible in this practice. I felt the deepest mudita of my life knowing the Clear Mountain pilgrims were hearing these teachings. I took my own vows and practice even more seriously and reinvigorated my intentions.

My own practice deepened while it also rose to the top of my experiences leading me onward with a new dedication. I felt supported not only by the pilgrims but also by all the pilgrims through the ages. Ajahn Nisabho’s and Ajahn Nyaniko’s talk on the call for openness to experience resonated. The pilgrimage led me out of my expectations of simply viewing and into allowing their pilgrimage to be part of my pilgrimage, not separate but alive and intimate.

The New Year’s Eve vigil firmed these nascent understandings even more. The silence following each of the 54 chants was potent. To me, it was a first hand enactment of the devotion and effort the pilgrims and Ajahns put forth bringing to life the fruit of the collective experience. I was left with a body of piti and a joyful heart. I felt joined with the entire sangha. That service and the silence afterwards bridged the Zoom/YouTube/ live separation and joined us in collective effort and celebration. I have lived many through many new years but this was the best.

My practice has been heavily based on the psychological aspects of the Buddha’s teachings. That night I knew reverence. Before the pilgrimage, I was a householder with a practice; now it feels like there is a practice with a householder.

I want to give deep and sincere thanks to the Pilgrims who underwent the rigors and ordeals of this pilgrimage to bring back their gifts of insights and growth.

I bow to the clarity of vision and depth of heart that would found a monastery on the understandings of this pilgrimage.